By Jim Austin

We’ve all experienced a variety of standing ovations following musical performances. Two are hesitant. There’s the begrudging kind: Oh, looks like everyone’s slowly standing; guess I gotta too, but it wasn’t THAT good. And then there’s the eager-but-cautious type: Oh, that was swell, but no one is standing so I guess I won’t … wait, there’s one … now two; let’s do this.

Then there’s the wildly enthusiastic variety. After the last note, the pianist’s hands hovering over the now silent keys. They slowly fall. And the whole place erupts, springing to their feet like doves flushed into a bright sky.

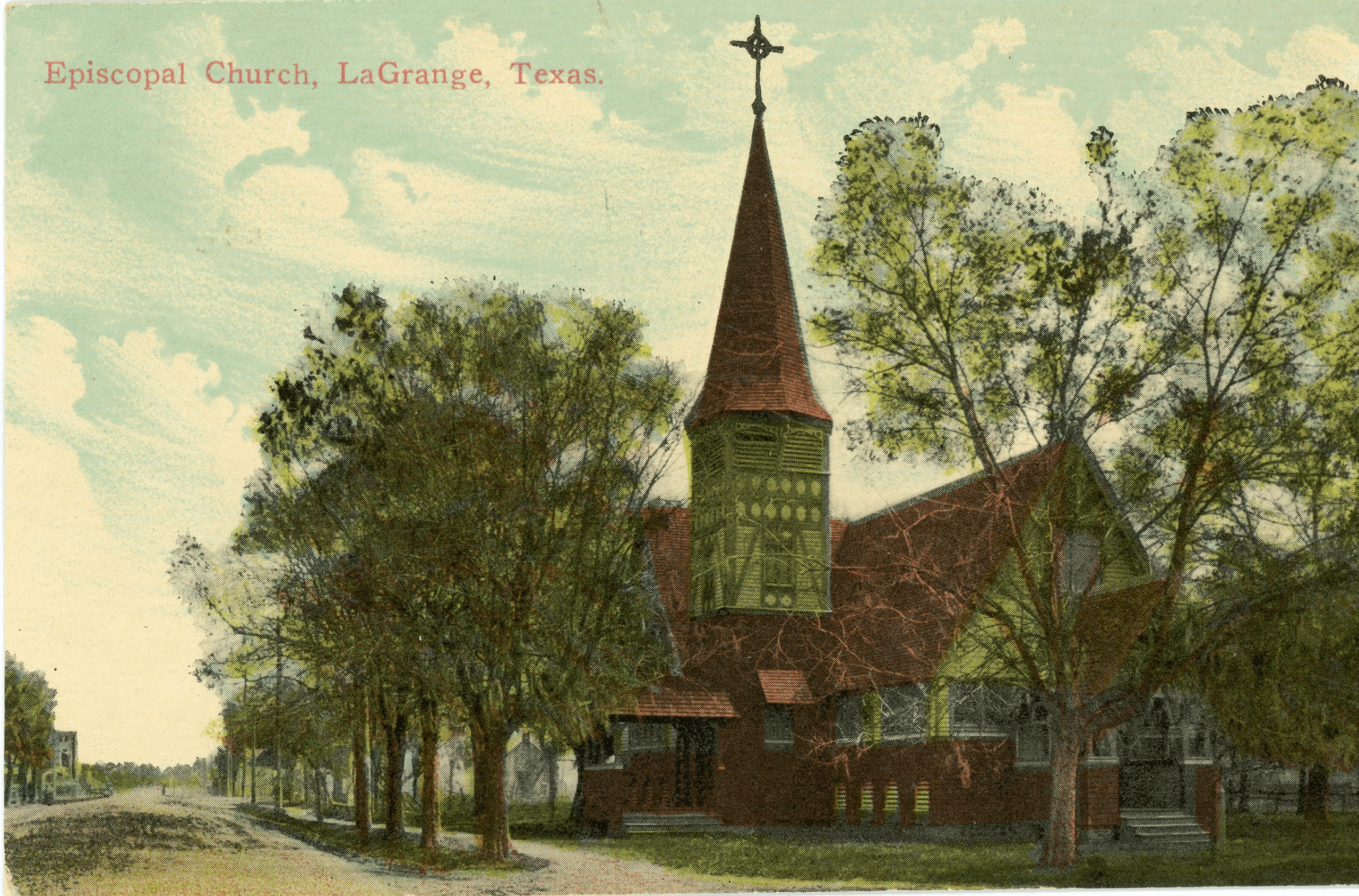

The latter was the culmination of the recital at St. James––which some have dubbed the concert church (across from H-E-B) –– Sunday afternoon.

The focus of the adulation? Miles Gillette-Bockhorn, the brilliant young, Fayetteville native who is creating a local following by his mercurial performances of classical piano works at the likes of ARTS and St. James.

During the concert Sunday, I noticed the faces in the audience––yes, I watch the faces as well as the artist; it’s a habit from my performing arts admin background. Rapt is the only word that fits. They were not simply pleased; they were enraptured.

Certainly, it was Miles’s masterly treatment of the Steinway that was at issue. First, he deftly caught the essence of the Liszt dark fifth rhapsody, not the more famous second––the “Tom and Jerry” cartoon one (which he sampled for us). He followed with Bartok’s 15 Peasant Songs,” that, as he told us, “Might not be for everyone.” Turns out, it seemed to be for everyone in the room. As for Miles, he was breathless after the frenetic and marvelous final Song.

But the wonders of the program were the final two Dohnányi rhapsodies, pieces and a composer probably new to almost all in attendance. How he wowed the listeners with the intricate pieces and how he managed to play them flawlessly from memory, without sheet music––well, we were stunned.

Thus, the instant standing ovation.

But it occurred to me, it was a bit more than just the artist. It was the acoustics.

I remembered my wife and my hauling a monstrous fifth wheel over the pock marked highways on the way to Santa Fe for the Chamber Music Festival. This was years ago when the venues there were black boxes, small churches like St. James. It was the sound, the acoustics of those structures that proved so thrilling.

La Grange’s St. James was built in 1885. Those fin de siècle churches––especially ones in the Queen Anne Revival style––were bereft of soft materials. No carpets, no wall hangings to baffle the sound. Instead, the architects use flat wood panels and glass (like the beautiful stained-glass windows of St. James).

These solid surfaces caused sound to reverberate. Some reverberation, as it turns out, is a good quality for transmitting the sound of music. Not so much for the human voice, of, say, a preacher. But preferable when it comes to a piano.

Anyway, the point is: the confluence of Miles’s magic at the keyboards with the richness of the notes emanating from the rictus of the Steinway with its lid fully opened … well, it makes for one of those memorable aesthetic experiences that satisfies the soul. And it makes the audience say, “we want more.”

And stand by; more of Miles is rumored to be coming in October.